In 1921, the Canadian scientist and physician Frederick Banting found that a protein isolated from the pancreas of dogs could lower blood sugar in human beings. “Insulin does not belong to me, it belongs to the world,” Banting, who sold the patent rights to his discovery to the University of Toronto for one dollar, enabling its widespread distribution, said. Before this breakthrough, physicians often recommended a near-starvation diet for children with Type 1 diabetes; one of Banting’s first insulin patients, a teen-age girl who had survived on extreme caloric restriction and weighed a mere forty-five pounds, began to thrive when given access to the medication, gained weight, and lived to the age of seventy-three.

In the early nineteen-eighties, the pharmaceutical company Eli Lillypioneered the manufacture of human insulin using recombinant DNA. Since then, Eli Lilly, as well as Sanofi and Novo Nordisk, have developed modifications of insulin, including longer- and shorter-acting versions. But the price of insulin has unaccountably surged. Between 2012 and 2016, it doubled in the United States, so that today it can cost diabetics as much as a thousand dollars a month. Eli Lilly in particular more than doubled the price of its blockbuster insulin analogue, Humalog, during the tenure of Alex Azar, who was then president of the company and is now President Trump’s Secretary of Health and Human Services. Roughly a quarter of people with diabetes take less than the amount of insulin they are prescribed because the drug is so expensive.

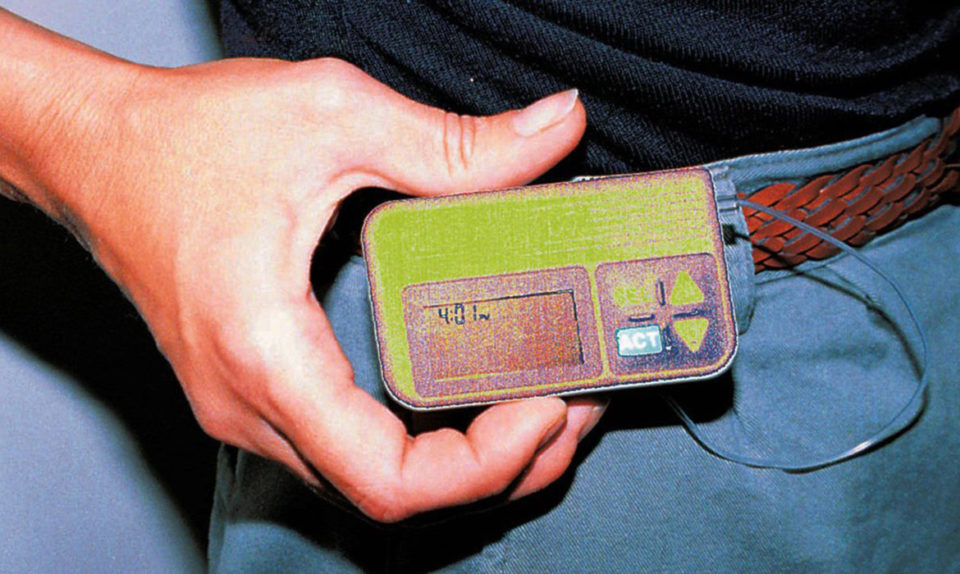

Sa’Ra Skipper, a twenty-three-old native of Indiana who lives not far from Eli Lilly’s global headquarters, in Indianapolis, is one of the millions of Type 1 diabetics who face this life-threatening bind. For years she has rationed insulin supplies, tried to limit her food intake, and shared medication with her younger sister, who also has the disease. She has also paid attention as rising drug prices have become more prominent as a political issue: the House Committee on Oversight and Reform has launched an investigation of skyrocketing drug prices, and the Senate Finance Committee will convene hearings on drug pricing next Tuesday. One congressional aim is to increase transparency around discounts and rebates, which primarily benefit intermediaries such as pharmacy-benefit managers rather than patients like Skipper, because companies use discounts and rebates to compete with each other rather than competing on the list price of the drug.